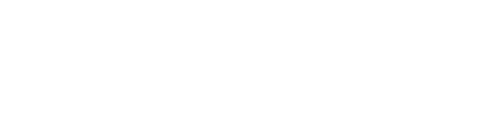

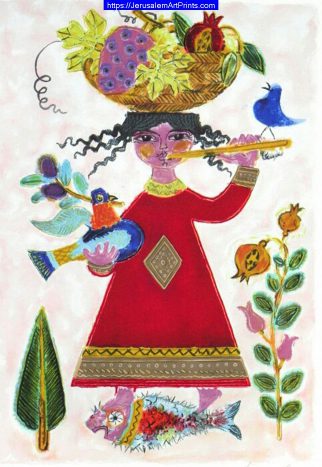

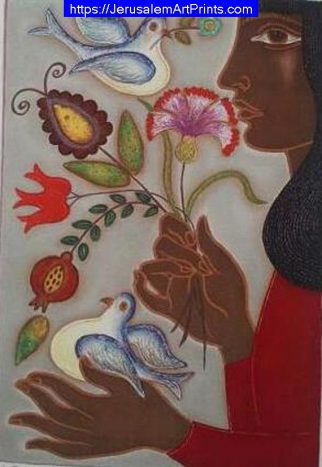

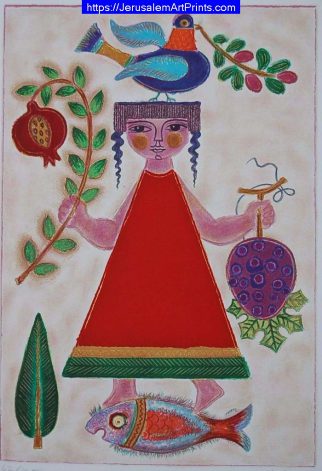

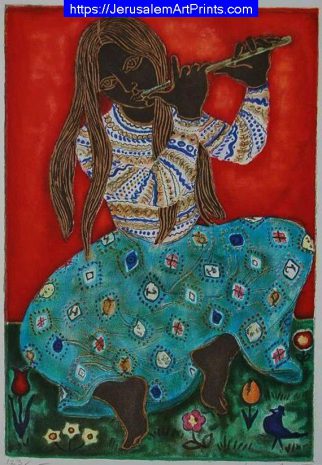

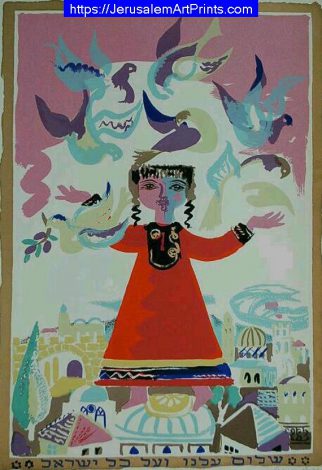

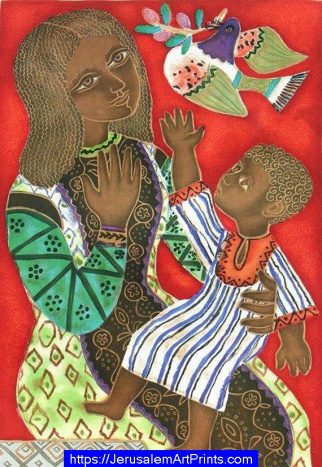

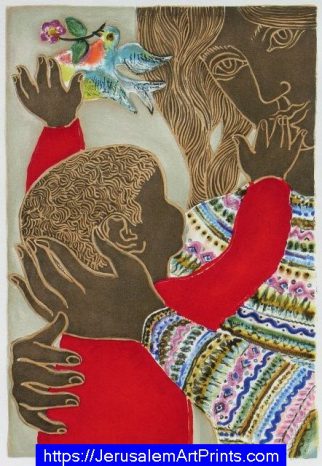

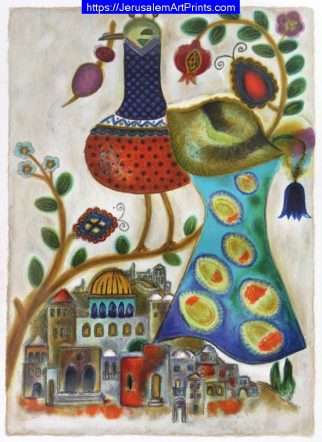

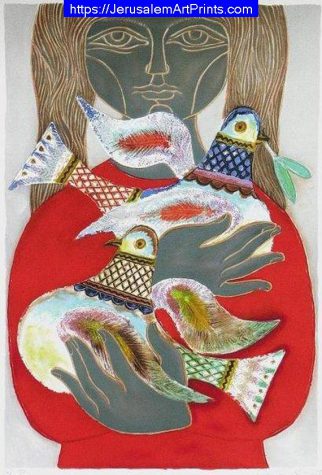

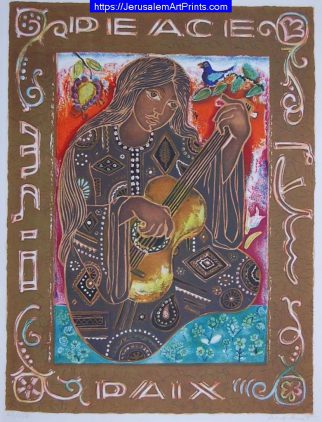

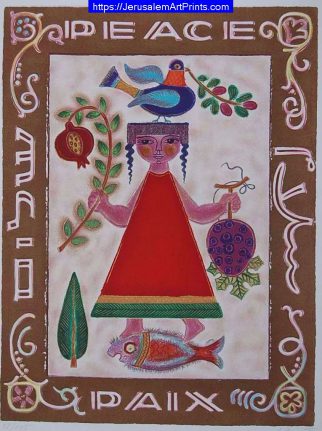

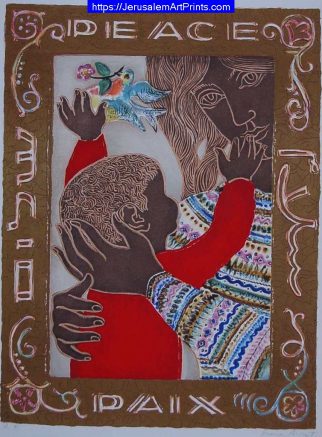

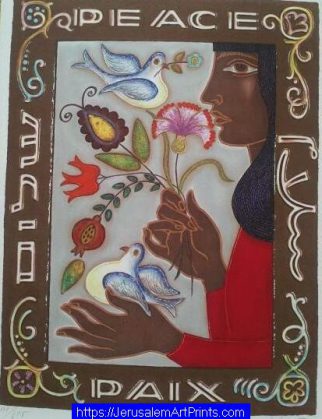

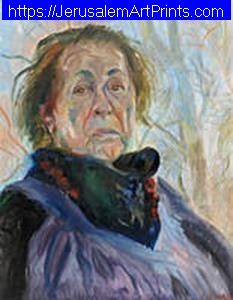

Peace Art – Irene Awret

In a Nazi Camp in Belgium, Irene Awret Found Salvation in Art.

Alone in a Gestapo jail cell with blood-stained walls, Irene Spicker — 21 and Jewish — was terrified. She had fled her native Berlin in 1939 and managed to hide for several years in Belgium. But by 1943, the Nazi persecution of Jews was in full force, occupied Belgium was no longer a haven, and her captors were determined to learn from her the whereabouts of her father.

Spicker had decided she could brave the uncertain fate of Jews facing deportation to Auschwitz. (Only at the end of the war would the full story of mass extermination efforts emerge.) But she would not put her father, who was in hiding, at risk — no matter the consequence.

And so she waited.

Spicker searched for some distraction to calm her fears. Luckily, the burgeoning artist still had her purse and the small sketchbook that she always carried. She proceeded to draw her left hand in careful detail.

It turned out to be a life-saving piece of art.

The Gestapo commander who arrived later to interrogate her was taken aback by the skillful drawing he found among her belongings. He abandoned his questioning and ordered her transferred to the transit camp at Mechelen — halfway between Brussels and Antwerp — where 25,000 Jews and several hundred Gypsies were processed before being shipped east to Auschwitz.

But instead of the short-term stay experienced by most detainees, Spicker would spend a year and a half at the Mechelen camp in 1943 and 1944. She was assigned to the art workshop, where a small group of prisoners painted cardboard identification signs, linen armbands and other posters and signs for the camp.

When the rudimentary tasks were done, Spicker was forced to paint portraits of Nazi officers. By choice — and in secret — she painted portraits of her fellow prisoners.

She also fell in love. Azriel Awret was another workshop artist, and he and Spicker married soon after Allied forces liberated Mechelen in September 1944.

Today, the Awrets live in Falls Church, where they each have home studios and still share a passion for the art that brought them together — and helped them survive the Holocaust. Irene, 83, fills large canvases with bold, vivid brush strokes. Azriel, 93, sculpts wood, clay and metal.

Irene has produced so much work that the overflow has made its way onto Azriel’s studio wall. “She has to pay rent for them,” jokes her husband. Russian-born and reared in Belgium, he is quieter than his wife, who takes the lead in telling their story.

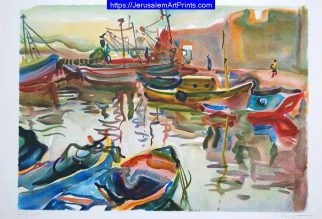

They were founding members of the Safed Artists’ Colony in Israel, where they settled in 1949 and raised two children before relocating to Northern Virginia in the ’70s. They’ve produced an array of public art, including ceramic murals at several Montgomery County schools, and Azriel’s sculptures adorn George Mason University’s campus.

Irene has also written a book, “They’ll Have to Catch Me First,” about her harrowing experiences during the Third Reich. It serves not only as a deeply intimate memoir, but also as a landmark historical account of Mechelen’s role in the Holocaust. Irene decided to write the book — which included traveling throughout the world to interview other Mechelen survivors — about 10 years ago when she met a young Belgian scholar from Mechelen (also known by the French name Malines) who had no idea that the transit camp existed.

The book also features art by the Awrets and other Mechelen prisoners. Irene managed to salvage some of the work after the camp’s liberation. The Awrets have long since donated it all to museums. The work is dominated, not surprisingly, by stark images of men, women and children who never returned from the transports to Auschwitz.

Hard though it may be to comprehend that art existed in such circumstances, Irene says she understands.

“Germans — even these people — have a respect for art,” she says. “It’s like you are some kind of magician.”

She recalls vividly how the camp commander would sometimes bring official visitors to the art workshop: “He would say, ‘These are our artists.’ ”

Irene adds that the very nature of artists will drive them to create, even in an oppressive environment.

“If you are a painter, you are very visual,” she says. “You have visual experiences, and you want to express them. It can be something very good, or it can be very sad. I was very young, and I didn’t think much of why I did these things. I see a child with sad eyes, so I want to do this.”

Had she known at the time, though, what became of the women and children at Auschwitz — how they were sent directly from the trains to gas chambers — Irene wouldn’t have painted their portraits.

“I couldn’t have done it if I had known,” she says plaintively. “Being a mother with children — helpless — it was the worst thing.”

The pain of her Holocaust experience, however, and the pain of learning afterward of the millions of Jews who perished, isn’t something she has chosen to explore overtly in her art, Irene says. But she is proud to help educate the public through her book about what transpired at Mechelen in those darkest days of World War II.

As for the future, she and Azriel are happy to simply continue making art, traveling when they can and enjoying time with their family and each other.

“One thing I’ve learned in my life,” says Irene, “is not to plan a long time ahead.”